Jason Zinoman's Shock Value and the invention of the modern horror film

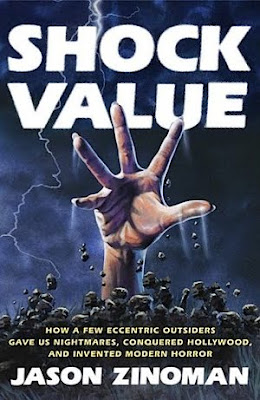

I very much enjoyed Jason Zinoman's Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror (Penguin Press). Written in the same vein as Mark Harris' Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollwood (2008), Shock Value left me wondering if Harris' study influenced Zinoman. Both authors pinpoint a paradigm shift in filmmaking history and then explore the individual creative choices that brought it about. Harris focused on the Best Picture nominees of the 1968 Oscars and the way they reflected seismic change in what the young baby boomers preferred in their movies. In Shock Value, Zinoman turns to the decade that spanned Rosemary's Baby (1968) to Alien (1979), and unpacks how horror evolved from the faded gothic melodramas of the 1960s (characterized by campy costumes, bats, crumbling buildings, and Vincent Price) to the more artistic highly influential films of the 1970s including Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Last House on the Left (1972), The Exorcist (1973), Carrie (1976), and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). In the process, Zinoman examines the creative processes of filmmakers such as John Carpenter, Brian De Palma, Tobe Hooper, William Friedkin, Wes Craven, Roman Polanski, George Romero, and Dan O'Bannon.

I very much enjoyed Jason Zinoman's Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror (Penguin Press). Written in the same vein as Mark Harris' Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollwood (2008), Shock Value left me wondering if Harris' study influenced Zinoman. Both authors pinpoint a paradigm shift in filmmaking history and then explore the individual creative choices that brought it about. Harris focused on the Best Picture nominees of the 1968 Oscars and the way they reflected seismic change in what the young baby boomers preferred in their movies. In Shock Value, Zinoman turns to the decade that spanned Rosemary's Baby (1968) to Alien (1979), and unpacks how horror evolved from the faded gothic melodramas of the 1960s (characterized by campy costumes, bats, crumbling buildings, and Vincent Price) to the more artistic highly influential films of the 1970s including Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Last House on the Left (1972), The Exorcist (1973), Carrie (1976), and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). In the process, Zinoman examines the creative processes of filmmakers such as John Carpenter, Brian De Palma, Tobe Hooper, William Friedkin, Wes Craven, Roman Polanski, George Romero, and Dan O'Bannon.

Some choice quotes:

"Night of the Living Dead was also proof for a generation of directors that you didn't need the support of a studio, big or small, to make an effective horror film that would attract large audiences. You didn't need money, much experience, or stars. You didn't even have to leave Pittsburgh. Film students noticed. Night of the Living Dead might never have received a huge national release, but it ran for years at small movie theaters and inspired countless directors to pick up a camera. It did for horror what the Sex Pistols did for punk."

"Rosemary's Baby was something relatively new: a horror film for adults."

[In 1969, Roman Polanski taught a film class concerning Rosemary's Baby for Arthur Knight]:

"Polanski focused on the nuts and bolts: lenses, angles, editing. Polanski explained that Rosemary's Baby was shot with handheld cameras and on the street, far away from the studio lot. It was important, he said, to keep the shots moving, and to use a wide-angle lens that slightly expanded the faces of his actors and the screen so he could sneak the horror into the corners of the frame. The oddness of this view could be exploited. He also said that he made sure to shoot a little askew. Characters' faces could be cut off. Only half of the action would be revealed, adding to the sense of unease. The scares would hover at the edges. Polanski explained that when using wide-angle there is a certain distance from an actor that still won't distort their face. It was a master class in the technique of horror. `From Polanski I realized,' said John Carpenter, a student in the class,`you really have to know what the f--k you are doing to make movies.'"

[When it came to fashioning the end of Rosemary's Baby, Polanski resisted studio pressure to show anything more than a] "final glimpse of a sinister pair of eyes":

"The Old Horror, the kind where the seats buzzed when the monsters appeared, required the payoff, but this film was never about the Devil. By not showing us the cartoon devil, Polanski removed the last traces of childish comedy, the final gimmick."

"Carpenter and O'Bannon were hardly experts in Freud or Heidegger, but they understood the importance of the vague, elusive power of an unseen horror through another source: the stories of H. P. Lovecraft, the reclusive misanthrope and literary godfather of the modern horror genre who wrote fevered tales with brilliants self-contained mythologies. His brand of terror he referred to as `cosmic fear.' Fear by itself can be unpleasant, but cosmic fear evokes an almost spiritual sense of wonder, of awe that is quite distinct from the shocks of cheap monster movies."

"The majority of horror and sci-fi films were not badly made," director John Landis says about the monster movies of the fifties and sixties. "They are not badly written, badly acted, or badly made--until the monster shows up. And then it's some guy in a stupid suit. The monsters are stupid and the plot is smart. That changed in the seventies when the plots became stupid and the monster smart."

"[Tobe] Hooper and [Kim] Henkel . . . met every night at Hooper's house and talked over ideas. They watched the original Frankenstein together as well as Night of the Living Dead. Hooper, building on the loves of his childhood, immediately thought of a dreamlike tale about the supernatural. `We referred to the way we put together as "nightmare syntax,"' Henkel said. Hooper liked this idea, but also wanted the movie [The Texas Chain Saw Massacre] to be funny, in a dark satiric way, a twisted spin on ordinary life. He had recently seen A Clockwork Orange and was drawn to the comic incongruity of the moral ugliness on-screen being played to the music of Beethoven and Singin' in the Rain. The beautiful, thought Hooper, can often be found in the horrible. He wanted the movie to be about how easy it is to shut off your conscience when stuck in extreme circumstances."

"Most of the time Hooper's point of view remains neutral. Before heading into the house for the first kill by Leatherface, the roaming camera sets up behind a blond girl on a swing. As she stands up and walks toward the house, it stays at a distance, showing us neither her perspective nor that of the killer inside the house. The insect-eye shot emphasizes the scale of the rickety two-floor building. We follow this victim, but at a distance. We are not getting assaulted here. With his camerawork, Hooper argues that the most frightening thing is to see terrible violence happen and know that there is nothing you can do about it. . . . Hooper puts you in the position of complete, mystifying helplessness."

"[Walter] Hill revered Howard Hawks and subscribed to one of his principles: `Have three good scenes and the rest of the time don't offend anyone.'" He liked the one scene in Alien's script when "an alien incubated in a person and then exploded out."

"What he [Brian De Palma] learned from Hitchcock was a film vocabulary. He discovered how to build suspense, how to trick audiences by making them identify with a character, and the singular usefulness of a shot from the point of view of a character. De Palma clearly borrowed from Hitchcock, but he also went much further with sex and violence, and he rebelled against him as much as his peers did. You can see this in the movie that began his most fertile decade of films, Sisters, released in 1973. Bernard Herrmann composed the music. After De Palma explained how he wanted the title sequence to be silent, Herrmann told him bluntly that would be a mistake: `Nothing horrible happens in your picture for the first half hour. You need something to scare them right away,' he insisted. `The way you'll do it, they'll walk out.'

`But in Psycho,' De Palma responded, the eager student, `the murder doesn't happen until forty . . .'

`You are not Hitchcock. He can make his movies as slow as he wants in the beginning. And do you know why? Because he is Hitchcock and they will wait.'"

"After Carrie,' Wes Craven says, "everyone had to have a second ending."

[Concerning Michael Myers' lack of a clear motivation in John Carpenter's Halloween (1978)]:

"Carpenter's firm belief, developed reading Lovecraft, watching The Thing, and in long discussions with classmates at USC, was that explaining ruins a good story. Influenced by the terror of Samuel Beckett, he wanted an empty space at the heart of the movie, where the answers usually are. The absence of meaning defined him. It wasn't that Myers didn't fit into the categories of cinematic killers with which audiences had become familiar. He didn't fit into any category. The mystery about this strange killer remained. In the credits, he was called simply `The Shape.' He was not supernatural, but not human either. He was the thing in-between."

"The central message of the New Horror is that there is no message. The world does not make sense. Evil exists, and there is nothing you can do about it."

Comments